[The article 'Krzyżowa - reconciliation in practice' was originally published in the MOCAK Forum magazine - a publishing project carried out by MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow. The text comes from issue 1/2020, which was focused on the challenges of education. We would like to thank the author and the publisher for the opportunity to publish the whole article in Polish. Below we present selected excerpts from the article translated into English. At the end of the page there is also a PDF file with the article in Polish].

[The article 'Krzyżowa - reconciliation in practice' was originally published in the MOCAK Forum magazine - a publishing project carried out by MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow. The text comes from issue 1/2020, which was focused on the challenges of education. We would like to thank the author and the publisher for the opportunity to publish the whole article in Polish. Below we present selected excerpts from the article translated into English. At the end of the page there is also a PDF file with the article in Polish].

Imagine a place where a dream has come true. In a former state farm, surrounded by dilapidated farm buildings and a palace with a hole in the roof, the leaders of two countries burdened with the trauma of war met. In a joint effort, Poles and Germans, supported by friends from other countries, created in this place - in the Lower Silesian village in Krzyżowa - an international meeting house.

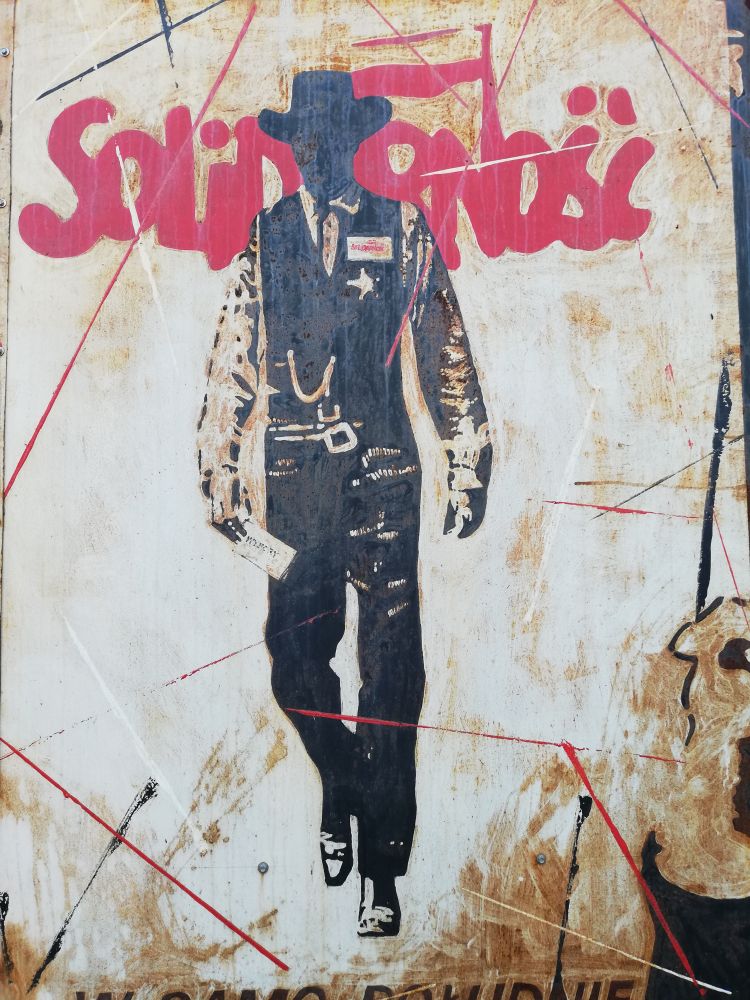

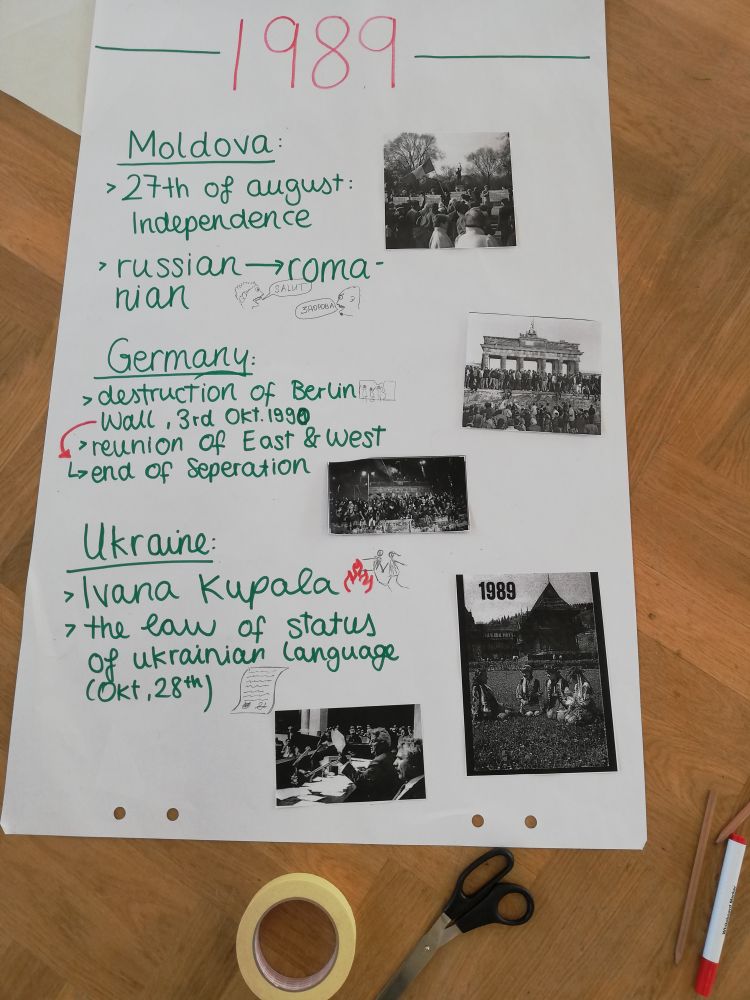

It was 1989, Poland was emerging from communism, Germany was on the road to reunification. Architects, engineers and gardeners began to build bridges across the divide - despite a difficult shared history, differences in legal systems, shortages of supplies, transport problems. The assumption was to work in international teams, although it would have been faster, easier with colleagues from one's own country.

Time played an important role. The idea of an international conference on the unusual history of Krzyżowa and the German anti-Nazi opposition active there - the Kreisau Circle - came from the Wrocław Catholic Intelligentsia Club. This meeting gave impetus to a civic movement aimed at establishing an International Meeting Centre at Krzyżowa. The idea seemed unrealistic to many at the time.

The conference ended on 4 June 1989, the day of the parliamentary elections. A few months later, it was decided that a reconciliation mass would be held at Krzyżowa with the participation of the new, non-communist Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki and Chancellor Helmut Kohl. The ceremony took place on 12 November 1989, just three days after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A fragment of the wall - like a monument - stands today next to the renovated palace.

The Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe has been operating for 30 years in the former manor house, which belonged to the German von Moltk family before the war. It organises numerous exchanges of school classes from Poland and Germany. Young people from Ukraine, Romania, Estonia, Bosnia and Serbia also come here. Foundation realizes annually over 100 projects, many in partnership with German association Kreisau-Initiative e. V. and other organisations in Europe. In Krzyżowa, bridges between people from different countries are being built every day.

Students from several continents took part in some educational initiatives, such as the simulation of the International Criminal Court. They played the roles of prosecutors, defence lawyers, judges and journalists and learned about human rights and the history of conflicts. For participants from Lebanon, South Africa, USA, Turkey, Armenia, Vietnam, Cambodia or Rwanda, among others, the Lower Silesian village of Krzyżowa was their first encounter with Poland. With interest, they watched young couples from the area having their wedding sessions on the grounds of the Foundation.

A huge square surrounded by an alley and the buildings of the former manor draws our attention. It is an agora, a market place, a centre. You can walk on the lawn, set up goals on it and play matches. This is where integration activities take place. The space has been organised in such a way as to encourage encounters with other people. There are no bans here, but an invitation to take responsibility for what is shared.

International meetings in a stable and a palace

The lawn is surrounded by buildings whose names refer to their former functions. Visitors are surprised when they receive keys to rooms in the granary or the stables. They eat their meals in the former cowshed (at the entrance there is a photograph of cows which used to live here, where the tables are now). For meetings they go to the former stables or the palace.

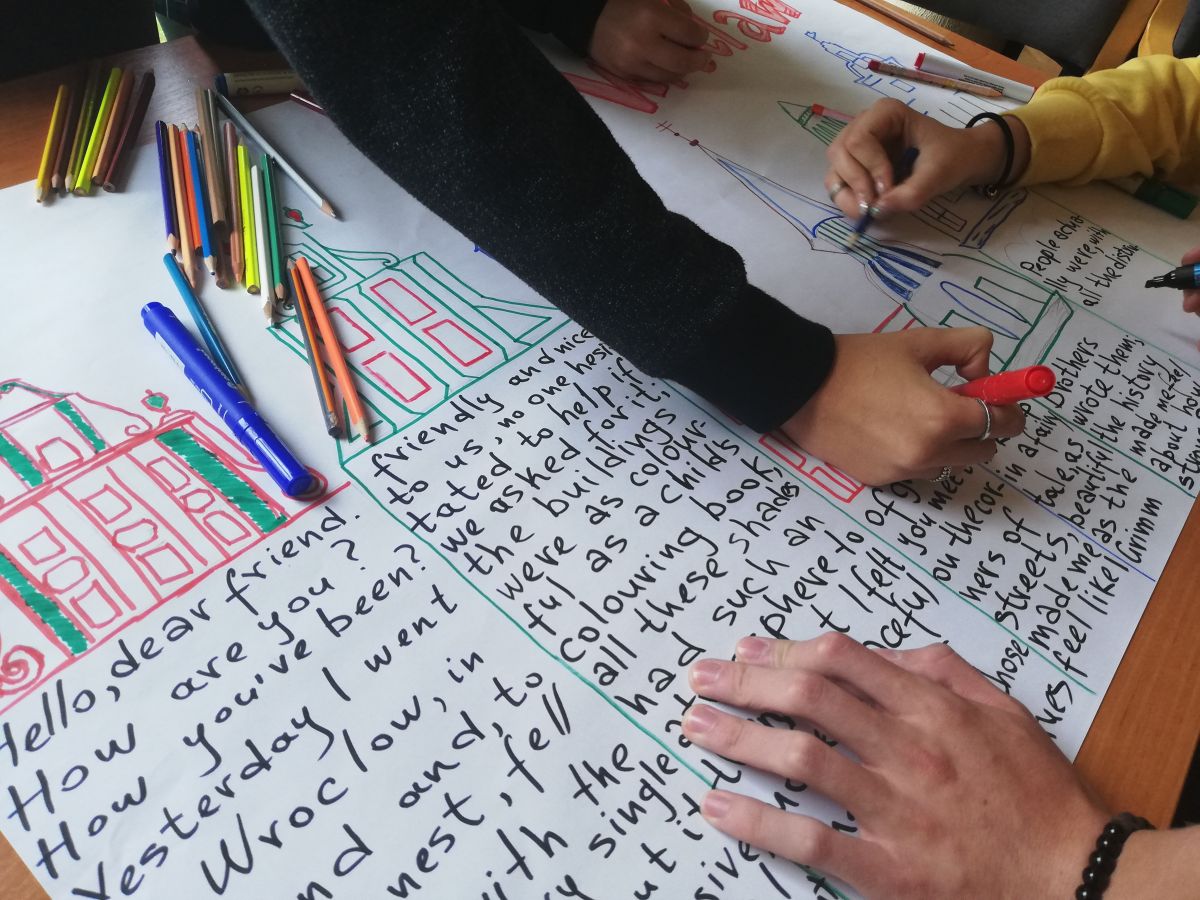

Non-formal education is based on the principle of voluntariness, it is based on the resources of the group, the contribution of all its members. It assumes the abandonment of hierarchy in favour of partnership and mutual respect. Trainers make sure that everyone finds a role for themselves in joint activities.

A separate issue in working with international groups is language animation, which aims at integration, support of communication and cooperation. They engage, encourage and reduce stress.

As a trainer, I appreciate the fact that the palace in Krzyżowa has become a place for educational activities. It is not a separate, intimidating place for special guests. It is for everyone: you can enter, you can touch the equipment, you can spend a break here without adult supervision. This fosters responsibility for the welfare of the community. People who are treated as trustworthy behave this way.

When I propose tasks in small groups during workshops in the ballroom, some participants sit by the elegant tiled cooker, others at the table with the gramophone, others by the fireplace. On the upper floor I have a room with a projector, a screen and modern rails on the walls, to which maps and charts can be easily attached. In the basement of the palace, young people meet after classes to play ping-pong or sing karaoke.

The role of the individual in history

(...) For German teachers, visiting the meeting place of the Kreisau Circle, which the German youth hear about at school, is an important reason for coming. While Polish groups tend to associate war-time resistance with armed struggle, they often learn about the Kreisau Circle only on the spot. They learn a new point of view: the heroes are the people who worked intellectually and planned the post-war social order.

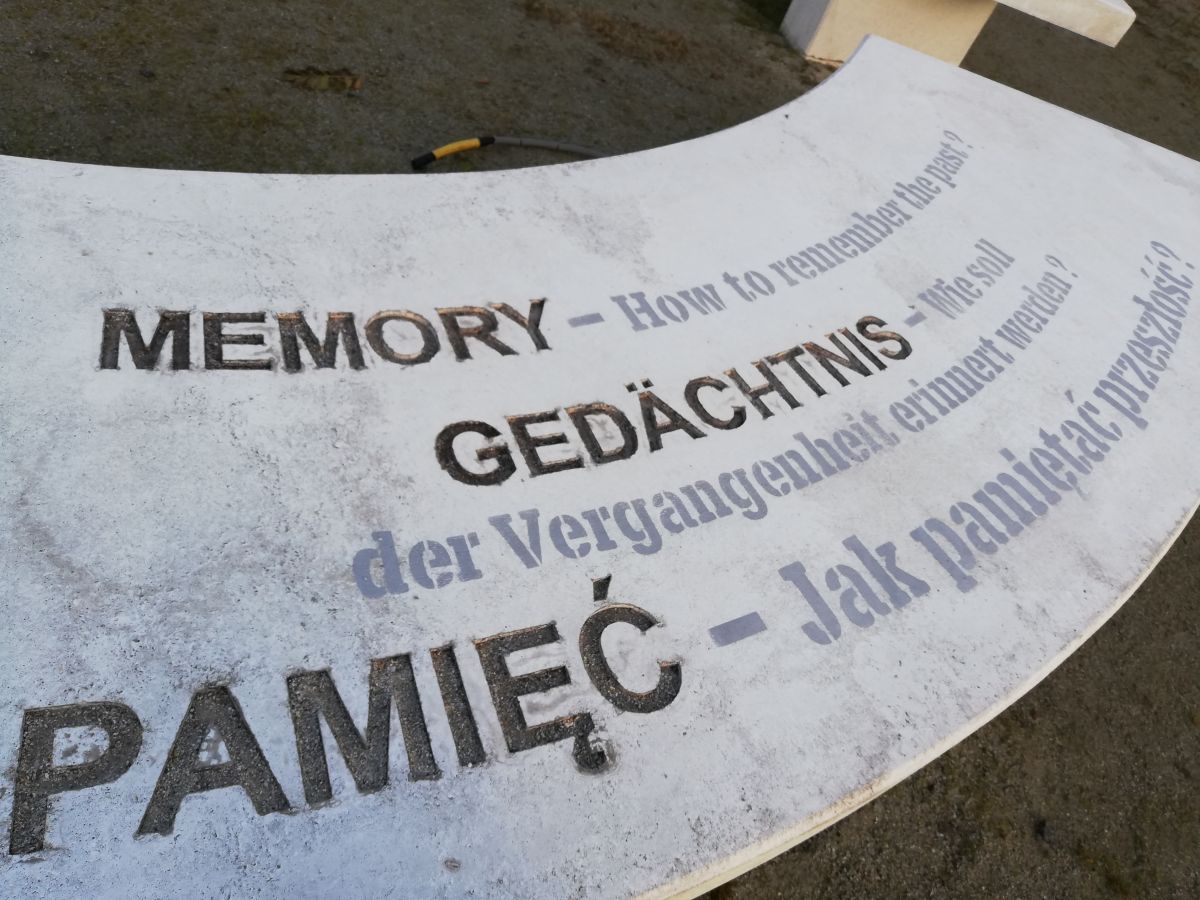

International groups also travel together beyond Krzyżowa. They discover the multicultural history of Wrocław. German groups sometimes ask to visit the nearby former concentration camp Gross-Rosen in Rogoźnica. Afterwards, we talk about what the young people from Poland and Germany remember, what moved them, what they learned - both on a factual and emotional level; what the words of a former prisoner of Gross-Rosen, to forgive but not to forget, mean to them.

During international projects for teachers and employees of educational institutions, which are devoted to the subject of the Holocaust, the groups spend several days in Krzyżowa and then travel together to Oświęcim. They visit the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum with a guide. The programme of the week-long project could be the subject of a separate study. Here, in a short review, I can only mention that it is necessary to devote time to building relationships in the group, substantive preparation, becoming aware of the motivation for dealing with this subject and the values which one wants to convey. It is also important to raise awareness of the facts of the past, still not present enough, marginalised in the dominant discourse of the countries the participants come from.

Courage and values

It is important, both with adults and with young people, not only to talk about the past, about the choices people made then, but also to create conditions for reflection on the challenges they face now, on the values in their lives. And encourage them to draw autonomous conclusions. During the workshops we talk about resisting evil, we initiate discussions. We ask, for example: "In what situation have you stood up for what is important to you? When did you show courage?".

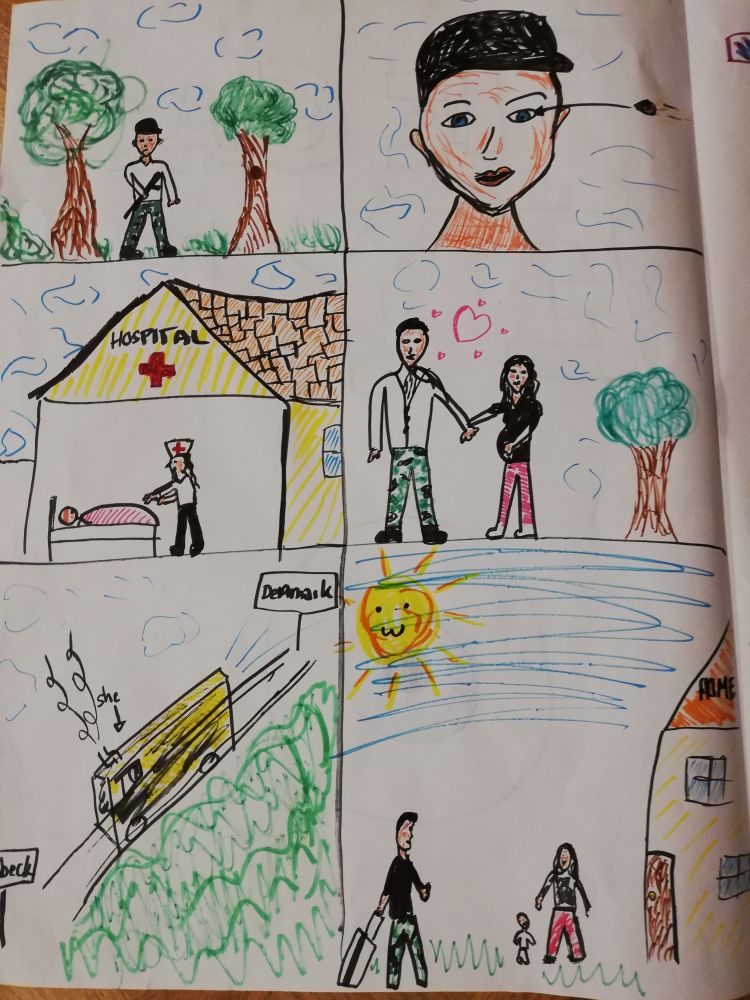

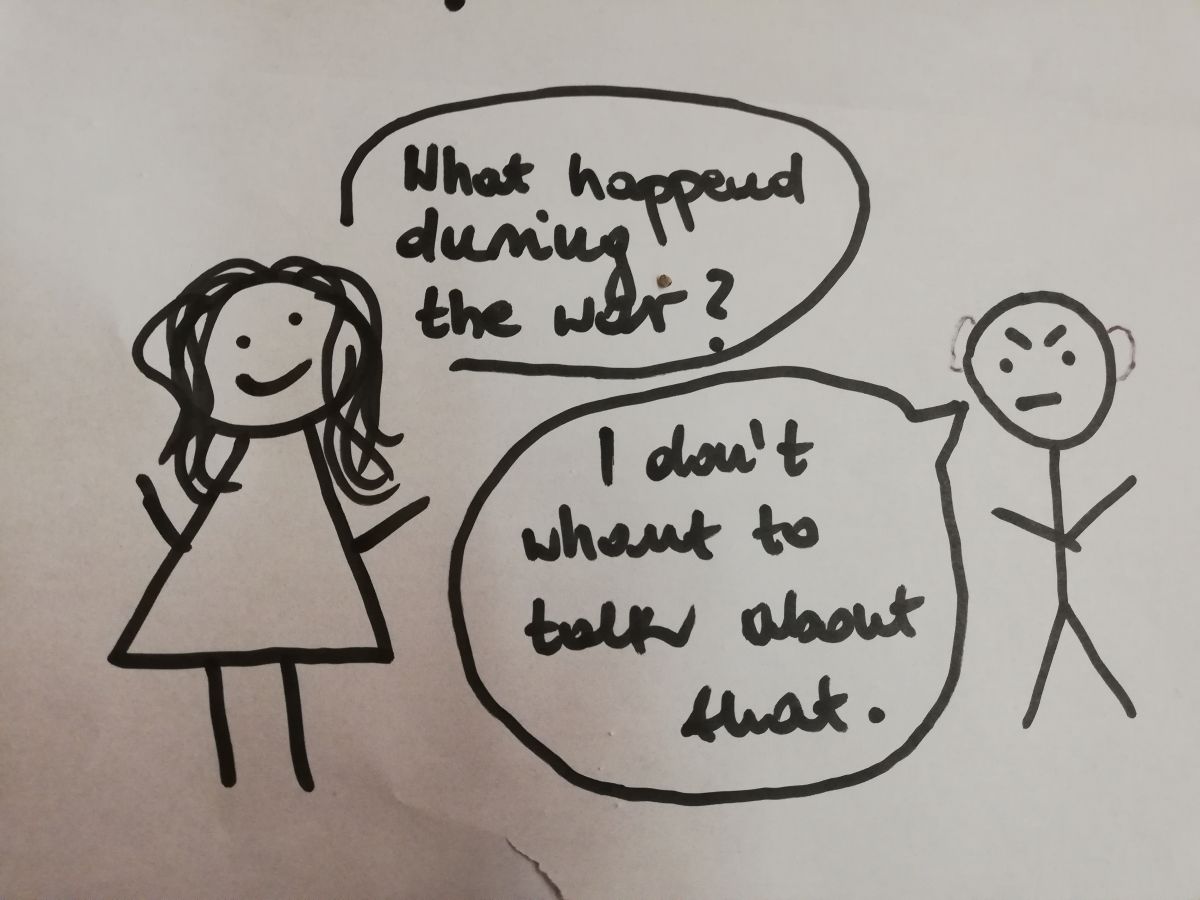

Young people share their own experiences in small groups and prepare theatre scenes based on their stories. We then watch them together. Someone defended a foreign colleague from a beating, another invoked the school statute so that the class avoided a third test on the same day, someone regularly takes part in demonstrations initiated by Greta Thunberg - the so-called "Fridays for Climate". We talk about the risks involved in standing up for one's values, about courage and the price one pays for it in times of peace and war. One of the participants - who chose to stand in front of the group alone - told us about his great-grandfather, a guard in a concentration camp. This was one of the moments when the audience recognises that their choice - openness, a gesture of acceptance or rejection - determines the quality of the time spent together. They are confronted with a sense of loyalty to their national community, to their ancestors and their tragedy. The next generation takes on the burden of reconciliation. They make decisions.

As a trainer, I witness public gestures - moving apologies for hurting another person, giving a second chance.

I see timid attempts to free themselves from the role of victim, to put aside the trauma of the family. As educators, we follow these choices, supporting with our experience what seems to serve the development of young people.

Collective memory

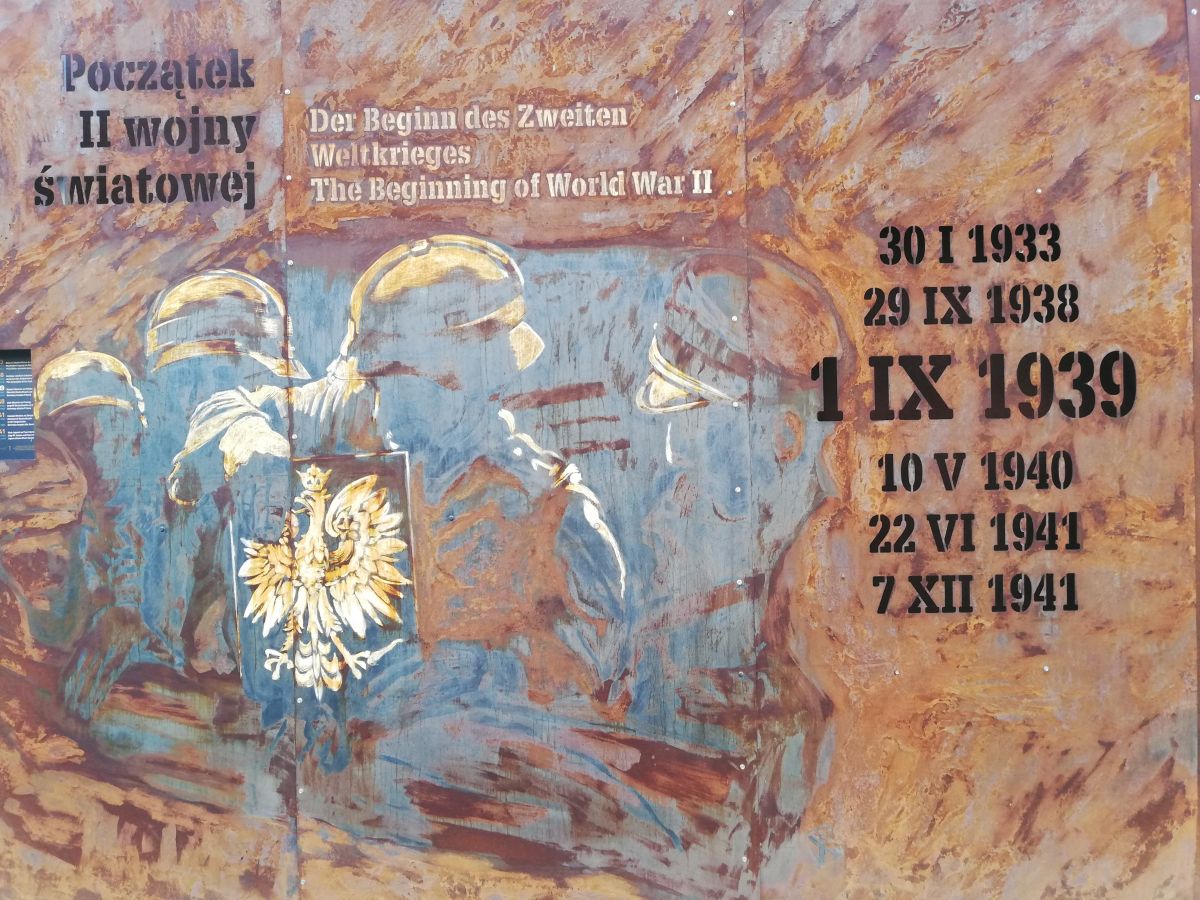

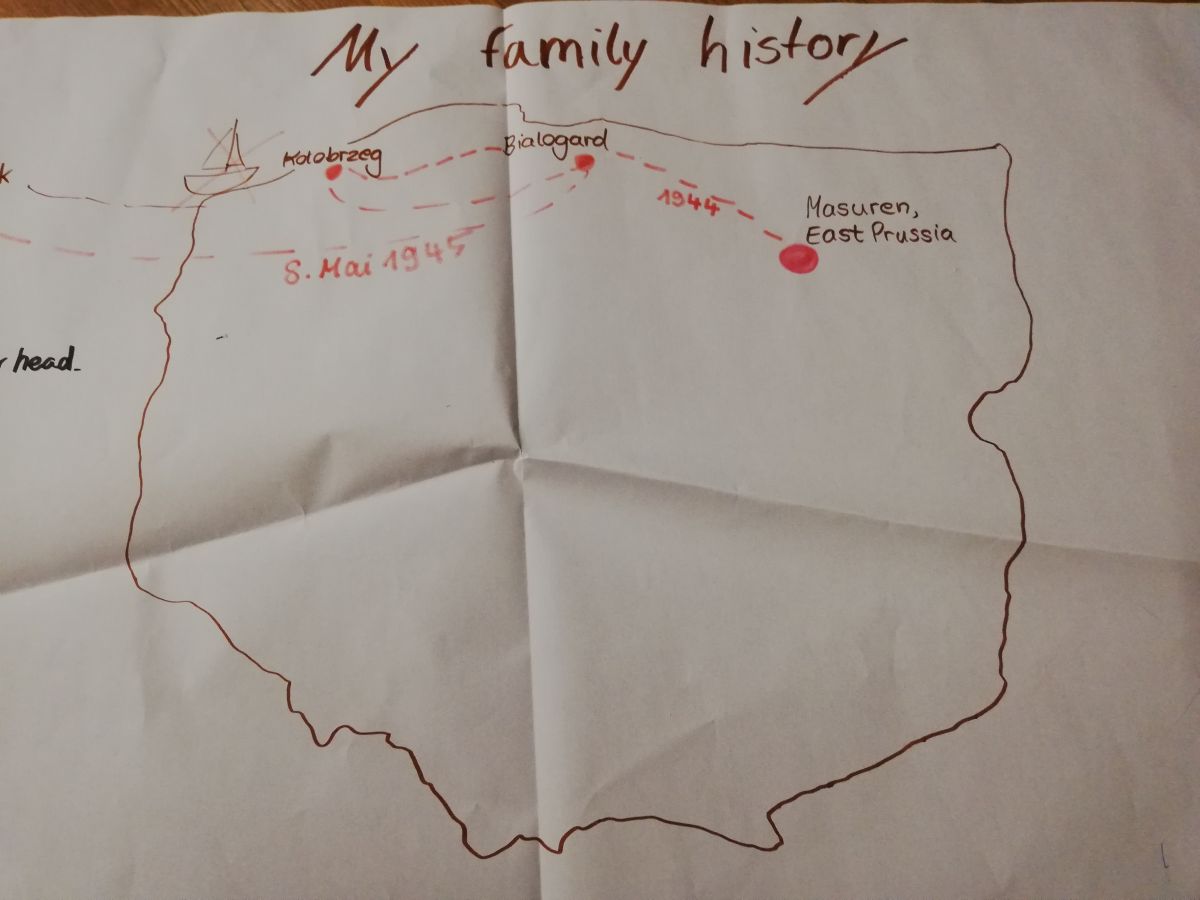

(...) During the workshop we ask where knowledge about the past can be found. There are many answers: museums, films, war songs, grandparents' stories, books, maps, the Internet. And of course school. Young people confront the narrative about the past from their textbooks and those of their peers from abroad. Events important for one country are given little or no attention at school in the neighbouring country. Why? Who is right? And who decides on the hierarchy of what is worth remembering? The meeting teaches critical thinking and problematises the perception of history as a science. (...)

Identity

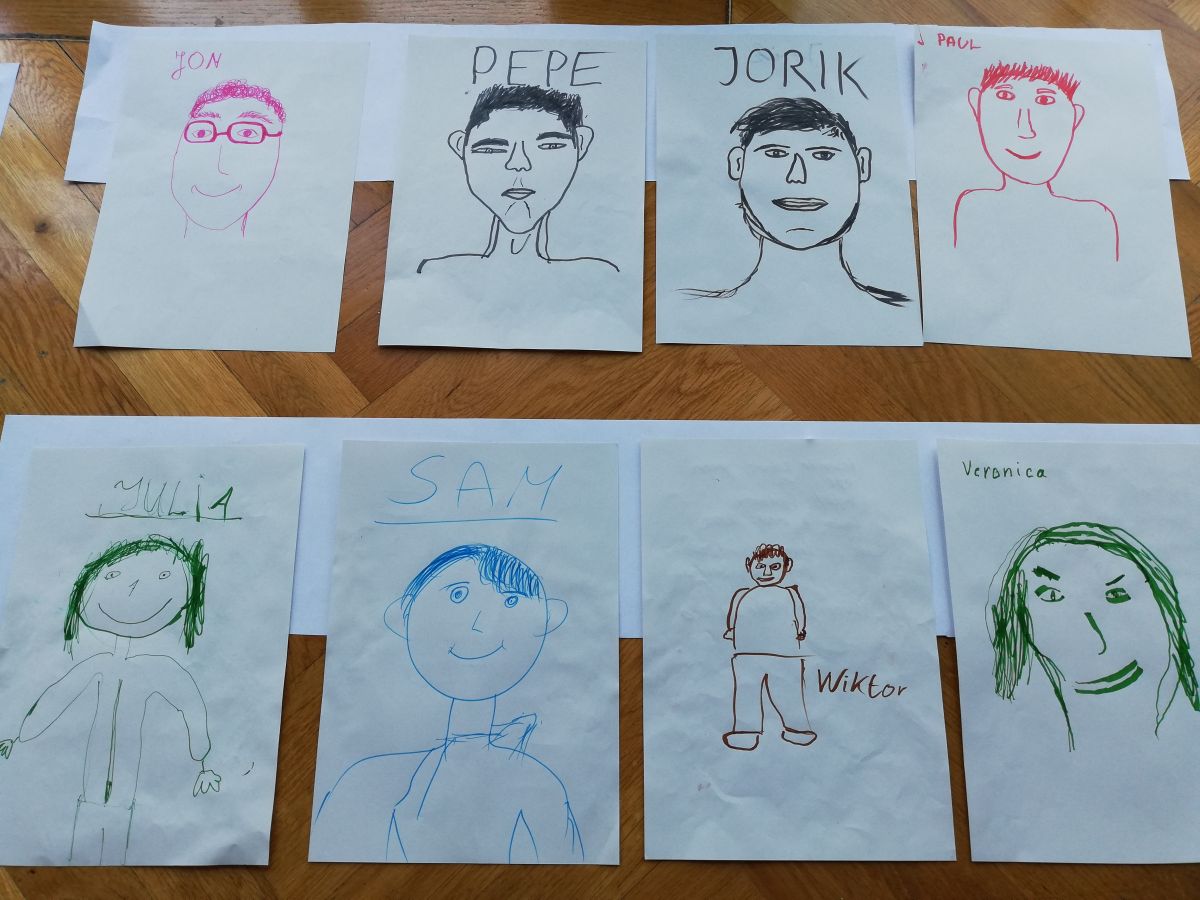

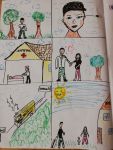

A popular practice in international youth exchanges is to organise a national evening. The groups present their countries, traditions and history. In the projects in which I participate, we break this pattern. We propose an evening with our own story - My Story Evening. Everyone is free to choose what and how they want to share. Some people present national dances (the Polish polonaise, Romanian dances in a circle and in pairs); someone brings a house booklet, into which parents have been saving for years, and which is now worth no more than a bottle of Moldovan wine. Someone else shows pictures of voluntary work in Siberia.

In the Flowers of Identity exercise, we reflect on our own identity, the elements that make it up and the conditions for its acceptance in society.

We wonder how belonging to a majority or minority community in a given place affects the identity of individuals and the way they remember the past. Each arriving group brings into the educational process the dominant collective memory of their country, as well as conflicts, including conflicts about identity, because "members of the group share ideas about the past, individuals belong to different social groups at the same time".

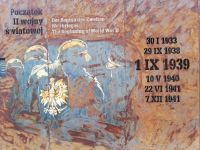

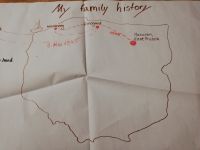

We would like to draw attention to the fact that the events of the past should be presented and analysed from many perspectives: states, local communities, families, individuals - in the spirit of the concept of entangled history by Michael Werner and Bénédict Zimmermann. That is why the Once upon Today... in Europe project involves people from six countries: Poland, Germany, Estonia, Moldova, Romania and Ukraine. We choose an event or a process about which everybody has heard: the beginning of the Second World War, the fall of communism and the political transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. We ask about the range of school information, family and personal experiences, we draw attention to similarities and differences. Participants from Estonia talk about singing patriotic songs together and about the "Baltic chain" which was created by Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians - together two million people - holding hands. Moldovans point to the rejection of the Cyrillic alphabet and a return to the Latin alphabet, Romanians mention violence and deaths in the streets, Ukrainians show pictures of fashion and talk about the way personal freedom was expressed through clothing in Soviet times and today.

Future

With regard to German-Polish exchanges, of which there are the largest number in Krzyżowa, some groups seem to be more interested in the past, while others direct their attention towards the present and the future. This is clearly visible during the question and answer round: "Everything you would like to know about Poland and the Poles (Germans and Germans) but have not had the opportunity to ask". Questions are asked about the memory of the Second World War, guilt and responsibility, mutual stereotypes. And also about the age at which you can get a driving licence, what you produce and whether there are exams for university.

After seven days of participation in the project in Krzyżowa, young people from Poland and Germany exchange addresses, sometimes they cry when parting and say that they will miss you.

Photo: Jolanta Steciuk

![]() MOCAK FORUM. Krzyżowa. Pojednanie w praktyce - Jolanta Steciuk.pdf

MOCAK FORUM. Krzyżowa. Pojednanie w praktyce - Jolanta Steciuk.pdf

Jolanta Steciuk - a graduate of the Faculty of Law at the University of Warsaw. As a scholarship holder at Columbia University in New York, she participated in the Historical Dialogue and Responsibility programme (2012). She is a trainer in international projects on history, memory and reconciliation carried out at the Krzyżowa Foundation for Mutual Understanding in Europe, including My History - Your History, Once Upon... Today in Europe, Entangled History as a Perspective for Non-Formal Education. Author of the interview with Halina Bortnowska Wszystko będzie inaczej (2010).

Issue 1/2020 of MOCAK Forum is still available for sale on the website: https://mocak.pl/mocak-forum